There is a rickety sign that says ROAD CLOSED at the intersection in front of the last ten miles to Johnson County. “Go around,” my sister says, matter-of-factly, immediately; the type of unassailable logic emitted by drill sergeants and mothers of Mississippi children. I hesitate, see the fresh glimmering patches of asphalt splashed over the rich red Georgia dirt, start to mumble about maybe there’s a bridge out or—“Go around,” she says again, flatly, the voice of someone who home-schooled two boys in a pandemic, who blew out her knees in competitive ice skating, who over the years has slowly replaced all her store-bought socks with ones she knitted herself. I don’t know any drill sergeants, but I know her, so I press the pedal down and veer around the sign.

We’re eight hours in and several hundred miles from our respective homes. Maybe the road’s not really closed, or if it is, surely the road crew will understand. After all, we’re on the way to a funeral.

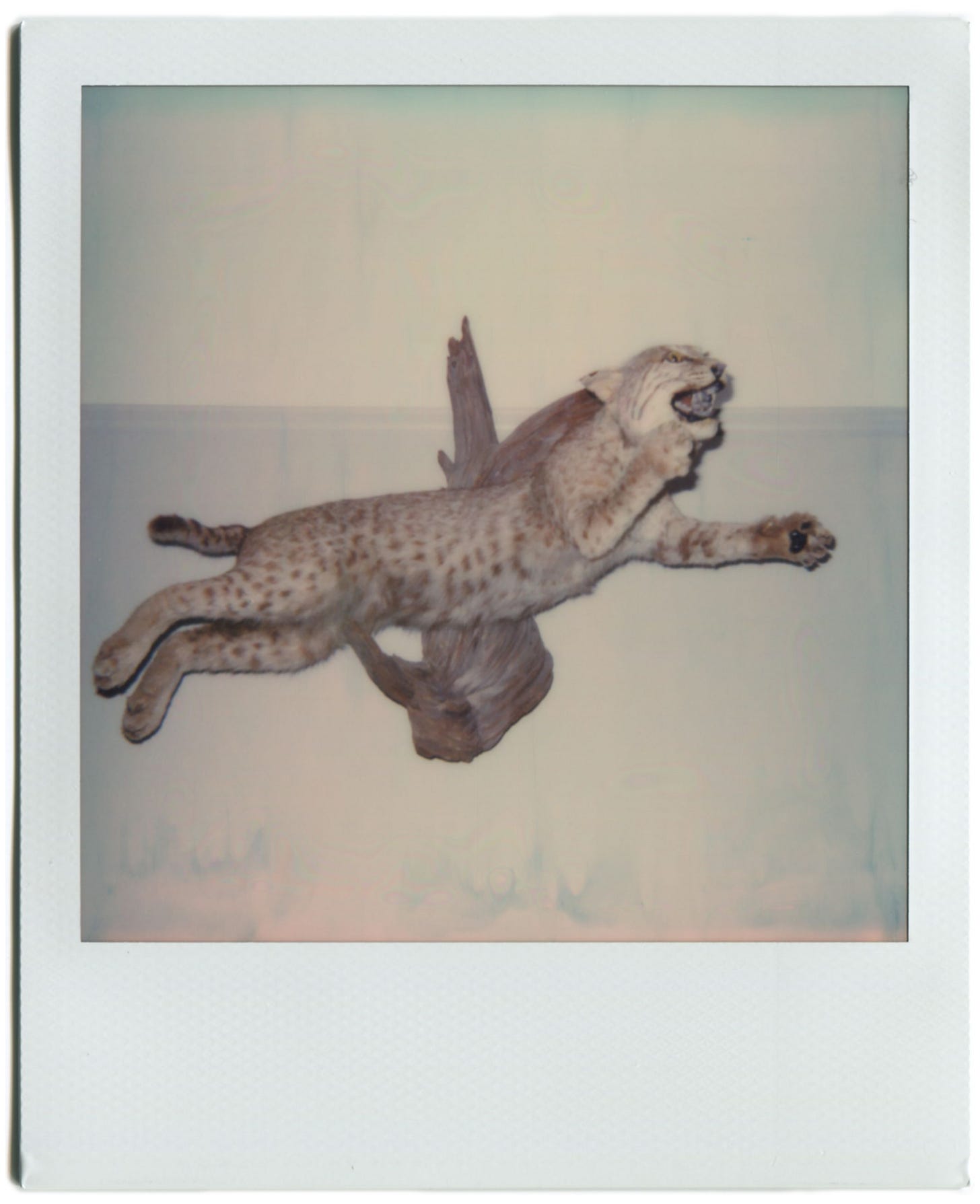

That there is a Polaroid of my Uncle Randy, or at least, the only one I ever took. I know it looks like a stuffed bobcat. Nevertheless, look into that wild snarl and the sheer ferocious joy in those eyes, and you’ll get it. I don’t make a lot of pictures of people, especially not family. I am not even really sure how you would begin to do it.

A BIG OLD BOY flags me down as we leave the house after the service. I forget his name. He asks if I’m the nephew in Jackson. I am, I say. He remembers that Randy told him he came to my graduation, and when was that? Opens a red Igloo cooler in the back of his truck, pushing aside ice and a bottle of Beam for a Pepsi in the can.

I turn fifty in three days. The old boy is thinking of something that happened over two decades ago. But I know the day well and think of it regularly. My uncle in a suit in the pews at First Baptist as they called out names and we walked across a stage, him sitting by my momma and daddy and stepmom and Nana. The governor did the speech. I can take you right to the hotel where he stayed so he could make it, right off I-55. In the trunk, he carried two crates of his records. For my graduation gift, he gave me all his music.

THE ROAD CREW is unmoved by our plight. They are standing on the shoulder in the sun, hot for February, heck hot for May, staring at me with blank eyes, shovels in hand. I recognize that we are at an impasse, I say, unfortunately without much politeness, but I would like y’all to understand that I am not wearing a suit and tie to go to the Mack-donald’s in Dublin. A scrawny kid with a beard down to his sternum is backing a little one-man compactor over the hot asphalt. I am going to a funeral in Wrightsville, and if we turn around and take the back way as you suggest, we will miss it.

One of the road crew spits. The supervisor suggests I have disregarded the rules of the road by ignoring the ROAD CLOSED sign, and that perhaps he should call a lawman. This pains me because I know it is true, and I am a rule-follower. There is some more discussion which may or may not have involved me invoking what I am honored to do for a living. We are not terribly far from Milledgeville and I am convinced these are the grandchildren and great-great-grandchildren of the narrow-eyed goons so bitterly lampooned by Flannery O’Connor. I know that is uncharitable and it pained me at the time to think it and I feel rather guilty about writing it now, but here we are.

In the end the road crew slowly shuffles off the shoulder, en masse, like some kind of one-celled organism reacting to a jostle of the Petri dish, their expressions never changing. I get back in the car and my sister immediately says “pulled the judge card out awful fast, didn’t you?” I don’t answer. The asphalt crackles as we ride over it, spackling the back end of the car.

Years ago Randy’s best records got mixed in on my main shelves, even got upgraded to fancy plastic sleeves. On the back of some, in my grandmother’s careful cursive, she had written his name. I can’t pretend to know exactly why, maybe he loaned them out to friends and she was insistent on getting them back, or maybe she knew they mattered to him.

To me the best ones are by the great thunder gods of his youth: Led Zeppelin, Lynyrd Skynyrd, Nazareth, Black Sabbath (but it’s Technical Ecstasy, the last and least of the original line-up’s glory days). As a metal fan, the great jewel is Rainbow’s Rising, with Ronnie James Dio on vocals. There’s some demigods and other heroes mixed in here and there as well, Billy Squier and Toto, Aerosmith and Steppenwolf, Styx and the Nuge, a couple LPs by Foreigner, what I’m convinced is my dad’s old copy of Hotel California.

It’s a treasure trove. I am sitting here on a Sunday morning, listening to the robins sing, not spinning any of the records but just looking at them, and just thinking about him, and where we grew up, and what it all means. I don’t have a word for it, don’t have any way to express it or get at the truth of it, can’t fit this within the frame of a Polaroid.

After the preacher finishes, and it is lovely and gentle and sweet—he is careful to emphasize, without using the exact phrasing, that he believes he will see Randy in heaven—next a song is played. We are outside and it is packed and the big old boys who carried his casket are still standing by it, the sun glinting off the chrome cursive A affixed to the side. I’m startled because the music is so dang loud, I mean it’s rattle-the-window loud. And it’s Ozzy.

Voices, he drones, a thousand voices, and the song goes on, and then a solo, then keeps going on. “What in the world, Randy,” I think. I start grinning, then laughing, and bow my head. See you on the other side, Ozzy wails, and ladies and gentlemen and other folk, there is a radio version of this song, but that’s not what we’re getting here today, graveside in the hot February sun in the State of Georgia in the United States of America, we are getting six minutes and two seconds of heartbreak, we are getting the album version, and we are going to listen until the end.

Maybe there is a word, a little word that can mean everything, one that’s sometimes smaller and sometimes bigger but always there, which expands and contracts and expands again as you age. Which explains why folk drive three states and try their hardest just to be there at the end, while maybe worrying they weren’t there enough in the middle. Maybe the only word is family.

FROM THE OBITUARY of Randall J. McCarty:

Mr. McCarty was born on July 27, 1959, in Fairfield, Alabama to the late Leonard Neil McCarty and Dorothy Casary McCarty. He was employed by Waco Electric. He loved hunting, fishing, rock-n-roll, and his Alabama Crimson Tide.

The car doors slam shut and I turn the air conditioner down like it is the summertime. Our shoes are covered in red dust. Are you okay? My sister asks. We are both vegetarians, had filled up on the dregs of a giant tinfoil pan of mac and cheese, some beautiful dark (almost purple) field peas, chess squares. I had sat with my cousins and told stories and laughed. There was a register on the island in the kitchen which recorded who had brought what, running to two pages:

Tommy & Dayna Logan, Chocolate Cake

Ray & Kay Outlaw, Zaxbey’s

Kevin - Rebecca, taco soup and banana pudden

Casey & Billy Ritch, Kentucky Fried Chicken

I turned on the radio and put the car in reverse. Pick us a different way back, I tell my sister. I don’t ever want to go down that same road again.

POSTSCRIPT.

On the morning of my birthday I make some coffee, read my devotionals, fill the mini crossword. I get up, a little slower than normal maybe, and crouch by the record shelves. I thumb through the Ls. I know what I’m looking for. The cover is hand-drawn, meant to look like a church window, but the band’s logo is made up of bones. The edges of the cardboard are frayed but it looks alright. I look for his name scrawled on the back. I drop the needle: it’s Side One, Track One, just as it should be.

One, two, three, Ed King counts off.

Turn it up, Ronnie Van Zandt says.

So I turn it up, loud enough to shake the windows.

Roll Tide.

“GORJUS” is a dispatch devoted to art and life in the South, held fast with instant film. If you liked what you saw and read, if you maybe felt a twang in your belly while you looked it over, then this is for you, and I reckon we would be friends. Consider sending this letter to a pal who is like us. I’m gorjusjxn on Instagram, and you can see an archive of Polaroids at McCartyPolaroids.

If you always stay until the end of the credits, maybe wait to see if there’s a little bit more, I’ll share that Randy was named in part for his mother’s brother. The twins in that story are his daughters; Randy was dark haired like his momma and uncle. Update: One of his daughters has made this Spotify playlist, and when I say I was shocked to see what was on it—well, this one hundred percent sums it up.

Roll Tide.

Happy Birthday, David! Eight years into the fifties, I can tell you from my perspective, 50 is freedom! I realized there were a lot of things that don't really matter and a few few things that really do. I chose/am choosing the few.

Come see us at Slow! We miss you there.

❤️❤️❤️